SESSION 7

CRYOBIOLOGY - I

Chairman: M. Toner

RESPONSE OF A LIVER TISSUE SLAB TO A HYPEROSMOTIC SUCROSE BOUNDARY CONDITION:

MICROSCALE CELLULAR AND VASCULAR LEVEL EFFECTSa

Sankha Bhowmickb, Chaouki A. Khamisb and John C. Bischofb,c

bDepartment of Mechanical Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 55455, USA.

INTRODUCTION

Cryopreservation of cells and tissues require the pre-loading of these systems with chemical

additives called CPAs (cryoprotective agents). The addition and removal of CPA from single cells

is fairly well understood and can be both measured with microscopy techniques and modeled with

irreversible thermodynamics as expressed in the equations of Kadeem-Katchalsky1. However,

there are still several challenges to modeling CPA transport in tissue systems, where unlike the

single cell, the membrane is only one of many resistances to transport faced by the CPA which

must ultimately enter the cell cytoplasm. In particular, the CPA must be transported through the

tissue a certain distance before arriving at a particular cell membrane. This transport and the

corresponding cell osmotic excursion, once the CPA effects are felt at a particular cell, are difficult

to measure and predict.

The purpose of this work was to obtain suprazero water transport data from the measurement

of volumetric shrinkage response of cells within an optically thick whole tissue slice exposed to a

hyperosmotic, non-permeating CPA, sucrose. We then try to explain the dynamics of cellular and

vascular volume changes by mathematical modeling which includes various resistances to sucrose

diffusion in the tissue matrix.

THEORY AND MODELING

Two models for the transport of sucrose through the tissue via an extracellular/ vascular

pathway were developed using a Krogh cylinder approach. For a one dimensional Cartesian case

the general species transport equation can be written

The first model proposes that sucrose transport into the tissue and subsequent cellular changes

can be interpreted by an effective diffusivity of species 1, sucrose. Since there is no reaction,

equation 1 then reduces to

A second model was proposed which assumes that water entering the vasculature from

cellular dehydration due to increased sucrose concentration leads to a bulk convective flux towards

the boundary of the slice. The Starling's equation is used to describe cellular dehydration due to

osmotic pressure difference created by sucrose in the vasculature similar to the freeze induced

dehydration as previously described3. The diffusion of sucrose into the tissue is thus coupled to

convection of water out of the tissue, due to dehydration. Equation 1 is rewritten for sucrose, with

no reaction, and it reduces to:

The two models are implemented numerically using a finite difference discretization scheme.

Boundary conditions included a constant sucrose concentration at one boundary and symmetry at

the centerline. The initial condition was zero sucrose concentration throughout the tissue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experiments were performed on freshly excised livers from Sprague Dawley male rats (175-

200g), (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana). Thin (~500µm) tissue slices were

subject to a hyperosmotic sucrose solution at 2°C (0.3M or 0.6M) for different time periods, and

slam frozen immediately after the experiment in liquid nitrogen. The tissue samples were then

freeze substituted,2 embedded in resin, sectioned and imaged under a light microscope fitted with a

digitizing system3.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

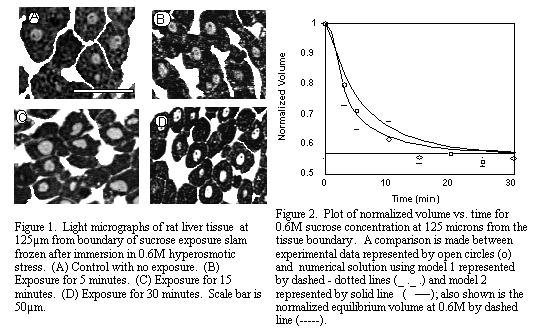

Image analysis of cellular and vascular/extracellular volumes was performed with NIH Image

softwareTM (NIH, Bethesda, MD) to ascertain cellular and vascular volume over time. Figure 1

shows the morphology of the liver tissue after 0, 5, 15, and 30 minutes of exposure to 0.6M

sucrose solution at 125µm from the constant sucrose concentration boundary. As shown in the

figure, individual hepatocytes appeared as a clump of dark stained polygonal structures with gray

round nuclei. The large white continuous areas between the cells correspond to the

vascular/extracellular space (predominately vasculature, 10.6% plus some interstitium, 4.9%).

The micrograph shown in Figure 1A gives a view of the liver cells in their control (normal) size

prior to sucrose dehydration. The micrographs in Figure 1(B, C, D) demonstrate the dehydration

trend exhibited by the continuous reduction in the areas of the cells as exposure time to hypertonic

stress is increased. In addition there was a change in the vascular volume too (denoted by the white

regions in the micrograph).

Figure 2 represents a comparison between the experimental and numerical data for 0.6M

sucrose at 125µm from the tissue boundary. The normalized cell volume on the y-axis is plotted

against minutes of immersion in the hypertonic sucrose solution on the x-axis. Experimental data

is represented by open circles, numerical solution using the first model is represented by a dashed-

dotted line, where Deff was estimated by the eye and had R2 > 0.97, and the normalized

equilibrium volume for a cell exposed to hypertonic 0.6M sucrose environment by a dashed line.

Deff jumps from a value of 0.16Dsucrose at 0.3M (data not shown) to 0.33Dsucrose at 0.6M.

These changes in effective diffusivity may be a reflection of the varying void fraction and

tortuosity of the tissue during cellular dehydration and vascular engorgement, thereby changing the

effective diffusivity4. The incorporation of these geometric changes inside the tissue appear to play

an important role in the hindered transport of sucrose and need to be incorporated into future

modeling attempts.

The second model is represented on the graph by a solid line. It tries to explain the hindered

diffusion of sucrose and corresponding cellular shrinkage in a tissue, by incorporating the effect of

convecting water which leaves the cells. The model captures the nature of the volumetric shrinkage

of the cells, being able to predict them within the error bars of the experimental value. However,

the 0.6M case underpredicts the volumetric shrinkage response in contrast to the results obtained

from 0.3M sucrose (data not shown), where volumetric shrinkage is overpredicted. This may be

an indication that factors in addition to convection, such as vascular compliance, need to be

incorporated for better prediction of the experimental results in future models.

CONCLUSION

Transport of a non-permeating CPA in liver tissue was studied by experimental and theoretical

techniques. The system consisted of a 20mm x 15mm x 500µm (thick) slab of liver tissue which

was exposed to culture media and hyperosmotic sucrose (0.3 or 0.6M) at the boundary. The

volumetric changes of cell and vascular spaces within the tissue slab at 125µm from one of the

symmetric boundaries was studied by slam freezing followed by freeze substitution microscopy.

The experimental data was then theoretically investigated using two models; one based on an

effective diffusion coefficient for sucrose, and another which incorporated the convective flux of

water out of the cells (and the tissue) while sucrose diffuses in. We estimate the effective diffusion

of sucrose as 16-33% of the actual diffusivity of sucrose in bulk water. The role of convection of

water out of the tissue is against the flow of sucrose and appears to be important in reducing the

effective diffusivity of the sucrose. Moreover, vascular compliance, porosity and tortuosity are

important factors that need to be considered while modeling transport in tissues.

REFERENCES

- Mcgrath, J.J. 1988. Chapter in Low Temperature Biotechnology: Emerging applications and

Engineering contributions, J.J. McGrath and K.R. Diller eds, ASME BED 10: 273-330.

- Robards, A.W., & Sleytr, U.B. 1985. In Low Temperature Methods in Biological Electron

Microscopy. (Chapter 7) Elsevier, 10.

- Pazhayannur, P.V., & Bischof, J.C. 1997. Measurement and simulation of water transport

during freezing in mammalian liver tissue, ASME Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 119:

269-277 .

- Geankoplis, C.J. 1993. Transport Processes and Unit Operations, Prentice Hall, Engelwood

Cliffs, N.J., 3rd. ed.: 412-413.

a This work was supported by a grant from Whitaker foundation to JB.

c Address for correspondence: Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Minnesota,

Minneapolis, MN, 55455, USA. Phone, 612-625-5513; fax, 612-624-5230.

ANALYSIS OF MASS TRANSPORT DURING

WARMING OF CRYOPRESERVED CELLS

Alexander V. Kasharin and Jens O.M. Karlsson

Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Illinois, Chicago,

Illinois 60607, USA

As a first step towards developing mechanistic models of damage to

cryopreserved cells during the warming process, an analysis of water

transport during warming was undertaken. With the aim of identifying

regimes in which conventional two-compartment, membrane-limited water

transport models will be valid for predicting cell dehydration/rehydration

during warming, the Peclet number was evaluated. Simulations showed

that Pe » 1 during the early stages of warming, indicating that transport

was rate-limited by diffusion to and from the membrane. However, by

comparing the time-scale of transport to the time-scale of the warming

process, it was possible to identify conditions in which the membrane-

limited transport model would yield adequate predictions in diffusion-

dominated regimes. Simulations suggested that a membrane-limited

model would fail during slow warming of rapidly cooled cells, but that it

would perform adequately if cooling was slow, or if warming was rapid.

METHOD OF DESIGNING PRE-FREEZING PROTOCOL IN

CROYOPRESERVATION OF BIOLOGICAL MATERIALS

Ryo Shirakashia and Ichiro Tanasawab

a Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo, 7-22-1 Roppongi, Minato-ku,

Tokyo 106, Japan

b Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Faculty of Engineering,

Mechanical Systems Engineering, 2-24-16 Naka-cho, Koganei, Tokyo 184, Japan

ABSTRACT

Procedures of determing the pre-freezing protocol in

cryopreservation of biological materials are discussed. In order to

cryopreserve biological materials, especially tissues with large sizes,

the concentration of cryoprotective agents (CPAs) should be high

enough after pre-freezing process, because a high concentration

CPA solution can be vitrified a rather low cooling rate. In the pre-

freezing process, the concentration of CPA is raised gradually to

avoid osmotic stress. In this paper, a conventional method of

designing the pre-freezing protocol is proposed. The rate of increase

of the concentration of CPA can be calculated on the basis of

Kedem-Katchalsky equations using the membrane permeabilities,

Lp, w and s. Optimal protocol can be determined by calculating a

process in which the normalized volume of the cell is kept constant

whole through the process.

INTRODUCTION

To cryopreserve successfully a biological material, especially a tissue with large size,

one would rather avoid the deleterious effects of cooling rate. When the cooling rate is

lower, the cells composing biomaterial suffer from solution effect or mechanical stress

caused by extracellular ice crystals. On the other hand, when the cooling rate is higher,

intracellular ice is nucleated which might break the cell membrane mechanically. These

phenomena suggest that only a certain narrow range of cooling rate permits high viability

of cryopreserved cells. Many researchers use CPA to get over this trend. Vitrification is

the ideal method, because the deletrious effects of cooling rate in the freezing process is

negligeble by avoiding ice nucleation. Fahy, MacFarlane, Angell and Meryman1 showed

that the glass transition occur even at a low cooling rate, if the concentration of CPA is

high enough (for glycerol around eutectic point). But, to introduce such a high

concentration CPA into cells, as well as into a tissue, is so difficult that efforts such as

searching new CPA (low viscosity, low toxicity), adding a pressure during freezing

process are made to reduce the concentration of CPA which can vitrify. In any case,

CPA should permeate through the membrane of cells without suffering from osmotic

shock. To avoid the possible effect of the osmotic pressure induced by a sudden change

of concentration of CPA, it might be effective to raise the concentration of CPA

gradually2. Moreover, pre-freezing protocol should be finished in a short period, because

the longer the pre-freezing period, the more degenerate biomaterial might be .

This paper proposes a method to design pre-freezing protocol using the membrane

permeabilities and size of cells, using Kedem-Katchalsky (K-K) equation as fundamental

equation. Similar researches were made by R. Levin and T.W. Miller3. We tried to

simplify the method of design, moreover, to assess whether the designing principle is

usable by applying the method to endothelial cells of porcine arteries.

DESIGN CONCEPT

As the large difference of concentration between intracell and extracell gives osmotic

stress, it might be effective to change concentration of CPA continuously. By solving K-

K equation numerically, the volume change of a cell can be predicted. Optimized profile

can be calculated by keeping bmin larger than bcri which is the normalized equilibrium

volume. According to the numerical calculation, the volume flux across the membrane

is nearly 0 through the pre-freezing process, that is, K-K equation can be simplified to

eqs. (1) as below.

Coa=Coa0+[waRT(1-blim)]/[sa(blim-e)2]*C1e0*(S0/V0)*(t-tmin) (1)

It is clear that among three membrane permeabilities, wa and sa is important for

optimizing the rasing rate of concentration.

PRE-FREEZING PROCESS OF PORCINE ARTERIES

To examine fundamental equations for design, porcine arteries were immersed in

glycerol solution of different concentrations, followed by estimation of viabilities of

endothelial cells. Two kinds of protocols were taken place. Viabilitiy which was

assessed by means of dye-exclusion test4 after each pre-freezing process is compared

with corresponding bmin calculated. The result shows a possibility of predicting damage

depends on pre-freezing protocol, so that design of optimal profile for pre-freezing

process might be possible. However, estimation of damaged cells should be quantified

more clearly, and also more reliable values of the membrane permeabilities and critical

cell volume bcri are required.

NOMENCLATURE

C : Concentration (mol/m3)

b: Cell volume ratio (m33)

R : General gas constant (J/(mol K) )

S :Surface area (m2)

t : Time (sec)

T : Temperature (K)

V : Volume (m3)

J : Flux through cell membrane ( mol/m2, m3/m2 )

Lp : Hydraulic conductivity (m3/(N sec) )

w: Solute permeability coefficient (mol/(N sec) )

s: Reflection coefficient

e: Non-osmotic volume fraction at noramilized osmolarity

I : Level of brightness

E : Mean value

V : Deviation

Subscript and Superscript

a : Cryoprotective agent

e : Electrolyte

o : Extracell

i : Intracell

0 : Initial state

V : Volume

cri : Critical value

lim : Minimum limit value

min : Minimum

rex : Relaxation

x : Axis along radius direction of a artery

y : Axis along axial direction of a artery

REFERENCES

- Fahy, G. M., D. R. McFarlane, C. A. Angell & H.T. Meryman. 1984. Cryobiology 21:

p.407

- Fahy, G. M., & S.E. Ali. 1997. Cryobiology 35: p.114

- Levin, R. L., & T.W. Miller.1997. Cryobiology 18: p.32

- Imahori, K., & T. Yamakawa et al. Eds. 1990. In Dictionary for Biochemistry (Seikagaku -

jiten), 2nd Ed., published by Tokyo kagaku do-jin : p.576, p.934 ( in Japanese)

|